What makes a reading program “work”?

On Success for All, reading research, and the "secret sauce" that facilitates extraordinary gains in student achievement

Greetings! This post is, in part, about education research, which is currently under attack. To stand up against damaging cuts to public education and to reading research, I invite you to join a call to action next Monday, March 24th — register here!

The latest set of episodes within Emily Hanford’s Sold a Story podcast begins with the following description:

There's a school district in eastern Ohio where virtually all the students become good readers by the time they finish third grade. Many of the wealthiest places in the country can't even say that. And Steubenville is a Rust Belt town where the state considers almost all the students "economically disadvantaged." How did they do it?

The district in question is Steubenville City Schools, which has also been the subject of Karin Chenoweth’s writing and reporting into that factors that enable some districts to achieve extraordinary student outcomes, particularly when serving student populations that have historically and persistently been marginalized within American schools and society.

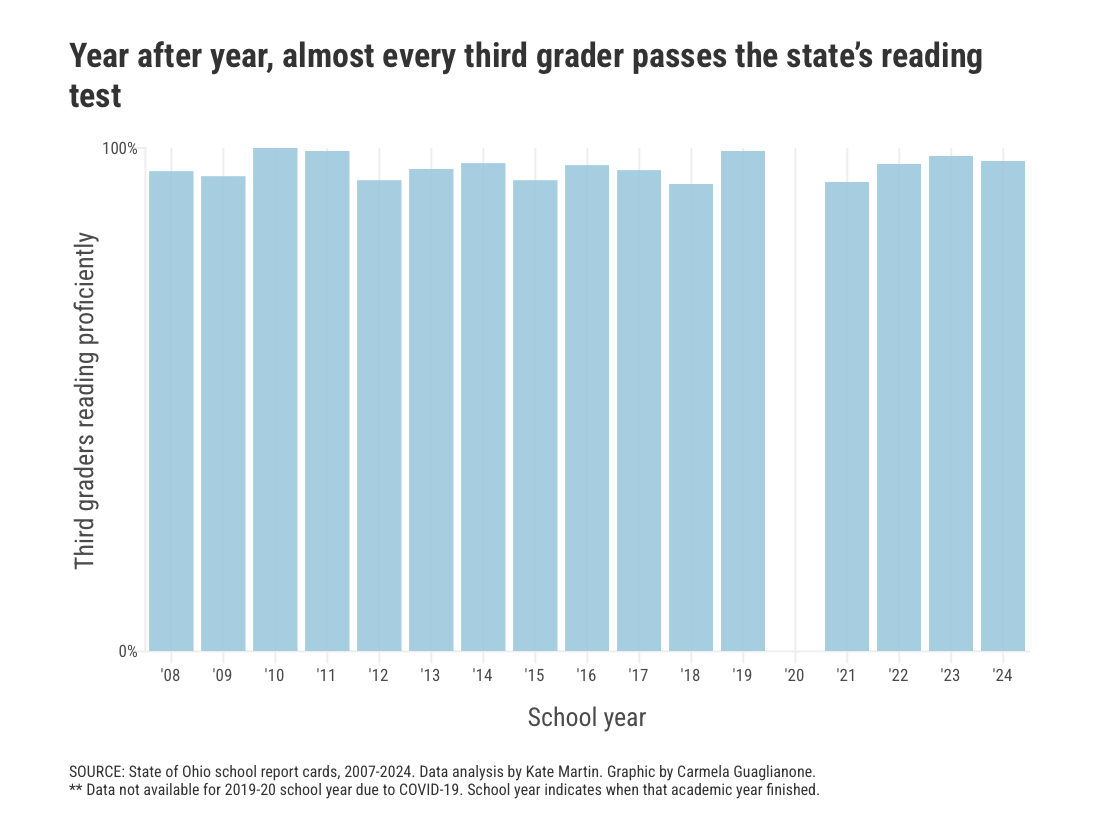

There’s a simple answer (well, sort of) to the question of “how did they do it?” The simple answer is that the district of Steubenville has been effectively implementing a research-based literacy program for over two decades, and that program has led to consistently excellent results, with between 93% - 100% of students in the district passing Ohio’s third grade reading test every single year (even post-COVID!) since 2008.

The reading program used in Steubenville is called Success for All, or SFA. It’s a program I know well, having initially been trained to use it as a first grade teacher, and later having supported teachers and school leaders with its implementation across a school system. SFA is designed as a “whole-school reform” model, which means it was developed to be more than just a reading curriculum, and also includes systems for assessment, supports for ongoing teacher and leader development, and guidance for family engagement. The model itself has been rigorously researched, with strong evidence of effectiveness for elementary school students, particularly on reading skills with the “alphabetics domain” such as word attack and identification (not-so-side note: studies like those conducted on the impact of SFA, whose results are housed within the digital What Works Clearinghouse of the Institute of Education Sciences (IES), are precisely the type of education research that is currently being defunded).

Hanford’s reporting illuminates a lot of the things that I loved about SFA, and which are part of its recipe for success. Here are a few highlights from my own experiences:

Everyone is a reading teacher: People tend to love this catch phrase, but the truth is it’s really hard to implement in practice. SFA makes it possible. The idea is that the whole school (or at least a subset of grades — let’s say K-2), teaches a 90-minute literacy block at the same time. During that time, classroom teachers and even specials teachers like the art teacher or science teacher can teach a group. This enables group size to be really small, especially for students who need the most attention and support. And because the lessons are so comprehensive and follow repeatable routines rooted in evidence-based instructional practices, teachers can quickly internalize how to effectively implement them.

Common destination, different starting points: The aim within SFA is to ultimately get all students to master foundational literacy benchmarks. But the program recognizes that students start the year in different places. Every eight weeks, students are grouped based upon their current mastery level, so they can be taught in a way that targets their exact needs. Students who need more intensive support can get smaller groups with the most expert reading teachers. Students who’ve already cracked the code don’t have to sit through direct instruction on concepts they’ve already mastered. Instead, they get to grapple with instruction tailored to their needs. And groupings are flexible. While all students are expected to grow a particular amount between assessment cycles, when students grow even more, they can leap ahead to group focused on more advanced content. If students don’t grow as much, they get additional support and tutoring. So no matter where students start or how fast they grow, the program supports all students in progressing toward a common destination.

Real parent partnership: One of the things I loved most about SFA was that students practice reading texts in class that are aligned with the program’s phonics scope and sequence. The texts are consumables, and travel back and forth with students so that they can read them in school each day and at home each night. By the end of a 3 or 4 day cycle with the same text, students are expected to be able to read the text with accuracy, fluency, and expression. Bringing the books back and forth enables parents to reinforce with their child the skills they are learning in school. It also enables them to see and support their child’s progress in real time. I’ll never forget my first weeks as an SFA teacher — not only could I see how much my students were growing, my students’ parents could see it, too. Celebrating their kids’ success was inspiring and motivating, and their partnership was an invaluable factor contributing to that success.

The bullets above provide a pretty decent answer to the question “how did they do it?” But they’re not the whole story. And Hanford illuminates this point in her reporting as well. Beyond these critical ingredients of the SFA recipe for success, there actually is a “secret sauce” of sorts at work in Steubenville. But it’s not a program or curriculum. It’s not a tech application or a special tool. It’s actually the ethos with which educators greet each student who passes through the threshold of a Steubenville City School: educators here unflaggingly believe that they are responsible for ensuring that every single student experiences success as a reader. They’ve never met a child they can’t teach. Their level of self-efficacy is remarkable. And it means that they don’t give up until every student in their care gets to where they need to go.

This is the same ethos I’ve encountered in every school I’ve ever been a part of that’s gotten extraordinary results. There is simply no substitute for the paired beliefs that (1) all kids can achieve at the highest levels, and (2) all the adults in this school community take ownership and responsibility for ensuring they do.

The neat thing about SFA is that it was designed with this ethos in mind. Hanford even quotes Nancy Madden, the education researcher who co-created the program with her husband, education researcher Robert Slavin, noting that the premise of the program was built upon the foundational belief that students will rise to the expectations we set for them . . .

. . . and the conviction that schools can generate excellent results:

SFA is not perfect to be sure. As noted within the What Works Clearinghouse report linked previously, the evidence base on the program’s impact on alphabetics far exceeds the program’s impact on other domains, including comprehension. This was my experience implementing the program as well. Its methods and approach for teaching foundational reading skills were transformative for my first grade students. The same could not be said for the elements of the curriculum aimed at strengthening students’ ability to make meaning of complex texts. At Success Academy, where I first encountered the program, we decided to focus on implementation of the components of the model that were generating results, and to discontinue and replace those that weren’t. That approach worked for us, in part, because our decision-making was grounded in the ethos I discussed earlier. For us, student success was never going to merely be about implementing a program that “worked” or didn’t. It was always going to be about the efficacy and the agency of the people implementing it.

There’s a Maya Angelou quote that proponents of evidence-based instruction often use to reinforce the importance of evolving one’s instructional practices to align with research: “when you know better, you do better.” That’s a good one, but I’m reminded of another Angelou quote that seems particularly fitting in terms of what it is that enables a reading program to “work”: “nothing will work unless you do.”

Schools and districts that achieve extraordinary results take this motto from an individual to a collective stance: “nothing will work unless we do.” Educators at these schools continually match their high expectations for students with equally high expectations for themselves. They may or may not use a program like Success for All, but, to be sure, they do their work in service of success for all students — and it makes a profound difference.

If you’ve made it to the end, thank you! I hope you’ll join a call to action to stand up for public education and stand up for reading research next Monday, March 24th. Spread the word and register here!

I continue to be fascinated by the requirement that at least 80% of the staff vote in favor of SFA implementation before adoption. Have often wondered what other curriculum providers could learn from that...

I was an SFA teacher for 5 years. I didn’t like the program and my school didn’t see results like Steubenville and you did. I do like the idea of whole school reform, and I think it is the people that make the difference. We just didn’t have that. Also, I’m curious about the demographics in OH. It looks like there is poverty but not as much of an ESL issue, and to me, that makes a huge difference. We had >90% English learners. Thoughts?